The Book of Mormon is written in the style of the King James Version of the Bible but contains many linguistic clues that indicate it has an ancient Hebrew source. Importantly, many of these clues are linguistic patterns missing from the Bible or undetected for generations, meaning the translators could not have just made it up or copied from the Bible. Here are a few of the dozens and dozens of linguistic evidences that indicate the Book of Mormon had an authentic ancient Hebrew source.

IF… AND STATEMENTS – The BOM contained many “If this.. and that…” statements instead of “If this… then that..” as is normal in English. Recently, scholars have discovered Joseph edited these out, changing them to “If.. then”. But it turns out “If… and” is correct – in Hebrew. If Joseph had known, why edit out an evidence for the authenticity of his claim? (Skousen, The Original Language of the Book of Mormon: Upstate New York Dialect, King James English, or Hebrew?, 1994)

IF… AND STATEMENTS – The BOM contained many “If this.. and that…” statements instead of “If this… then that..” as is normal in English. Recently, scholars have discovered Joseph edited these out, changing them to “If.. then”. But it turns out “If… and” is correct – in Hebrew. If Joseph had known, why edit out an evidence for the authenticity of his claim? (Skousen, The Original Language of the Book of Mormon: Upstate New York Dialect, King James English, or Hebrew?, 1994)

CHIASMUS – These poetic parallelisms went unnoticed in the BoM for a century. Again, if planted deliberately, why not reveal them yourself to add to your claim of authenticity? Turns out Chiasmus were nearly unrecognized in western literature in 1829, and Joseph and his scribes probably never heard of them. (Welch J. W., How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829 When the Book of Mormon Was Translated, 2003)

THE PROPHETIC PERFECT – The Book of Mormon prophets oddly sometimes speak about events in their future as if they were already in the past. Early prophets Lehi and Nephi seemed to do it out of rote when they said “I have obtained a land of promise” before arriving in the land of promise, or “the Holy Ghost descended upon him in the form of a dove” before the birth of Christ. It turns out this speech pattern was a way ancient prophets would indicate a prophecy was so certain that it might as well be spoken of in past tense. As generations of Book of Mormon prophets became more removed from ancient Israel’s culture, this pattern apparently became more unusual, until it reached the point that when Abinadi used it, he had to explain its usage to people. (see Mosiah 16:6) (Parry, Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon, 2002)

PLURAL AMPLIFICATIONS – Ancient Hebrew would “emphasize” an idea by pluralizing it – salvation becomes “salvations” etc. The English translation of the Bible, however, makes it singular. The Book of Mormon contains many instances of plural amplification instead of the expected singular – a trick Joseph couldn’t have known from copying the Bible or other alleged source texts. (Parry, Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon, 2002)

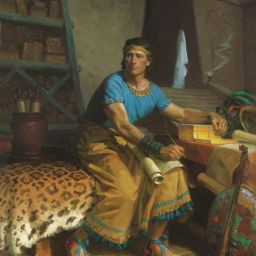

MISTAKES OF MORMON: THE CONSTRUCT STATE – Another Hebraism, the construct state can sometimes sound wrong in English, but correct in Hebrew. Sometimes Mormon “corrects” himself into the construct state (making it sound wrong to English speakers) instead of leaving it sounding perfectly fine in the English grammar pattern. (example: Alma 54:3) The construct state appears hundreds of times in the Book of Mormon and is used more often than the regular English syntax. (Parry, Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon, 2002) (Tvedtnes J. A., The Hebrew Background of the Book of Mormon, 1991)

ALMA AND SARIAH – Alma was thought of as a female name in Joseph’s time. Only a century after the publishing of the Book of Mormon was it discovered to be a valid male name in ancient times. (Yadin, 1965) Similarly, Sariah was known from the Bible as a male name, until the discovery of the Elephantine papyri. (Tvedtnes, Gee, & Roper, 2000)

OTHER NAMES – The BoM contains authentic Hebrew names including Sariah, Alma, Abish, Aha, Ammonihah, Chemish, Hagoth, Himni, Isabel, Jarom, Josh, Luram, Mathoni, Mathonihah, Muloki, and Sam—none of which appear in English Bibles. (Tvedtnes, Gee, & Roper, 2000)

PATRISTIC NAMES – The naming of a son after his father (Nephi son of Nephi, Alma son of Alma, etc.) was unknown in the Old Testament, however an ostracon from the time of Lehi has proved that such naming conventions happened in the area of Jerusalem from the appropriate time period. (Deutsch & Heltzer, 1995) (Tvedtnes, Gee, & Roper, 2000) Moreover, the appellation “the younger” to patristic names was used in Mesoamerica, just as it is seen in the Book of Mormon. (Palka, 2010)

EModE – The Book of Mormon is written in “Early Modern English” which is the language of the King James version of the Bible. While it’s easy to assume that Joseph was just copying the style, the BoM contains some EModE syntax NOT contained in the Bible and therefore inaccessible to Joseph. (Skousen, The Original Language of the Book of Mormon: Upstate New York Dialect, King James English, or Hebrew?, 1994)

UTO-AZTECAN – One researcher reports finding over 1500 shared “cognates” between ancient Hebrew, Egyptian, and the Uto-Aztecan family of languages. For a language to be considered a part of the same “family” historically it has only required a few hundred shared cognates. By that standard, one would say that perhaps some of the languages in the Uto Aztecan family should be considered a family born of an earlier Hebrew Egyptian hybrid. Even if the author has let his enthusiasm get away from him, the sheer VOLUME of commonalities should give pause to any serious researcher. (Stubbs, 2015)

UTO-AZTECAN – One researcher reports finding over 1500 shared “cognates” between ancient Hebrew, Egyptian, and the Uto-Aztecan family of languages. For a language to be considered a part of the same “family” historically it has only required a few hundred shared cognates. By that standard, one would say that perhaps some of the languages in the Uto Aztecan family should be considered a family born of an earlier Hebrew Egyptian hybrid. Even if the author has let his enthusiasm get away from him, the sheer VOLUME of commonalities should give pause to any serious researcher. (Stubbs, 2015)

ROBBERS AND THIEVES, OH MY – The King James Bible makes no distinction between “thieves” and “robbers,” but, according to the editor of Jewish Law Annual, ancient Jewish law makes it clear that robbers are typically organized groups, rivaling local governments, attacking towns and extorting ransoms with sworn oaths. Thieves are just people who steal. Unlike the Bible, The Book of Mormon is perfectly distinct in how it treats each class of criminal, as if it were written by somebody very clear on Jewish Law. (Welch J. , 1992)

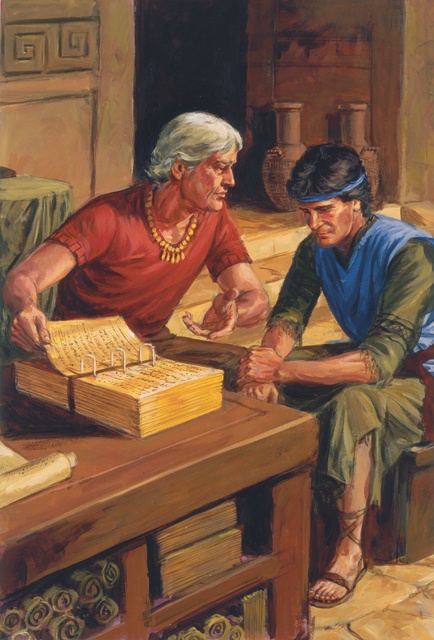

REFORMED EGYPTIAN – Book of Mormon writers use the phrase “reformed Egyptian” to describe their writing style and explain that it is the Hebrew language written with Egyptian characters. Anybody who has learned Japanese and had to transliterate their name into katakana knows what this is like, but was this a valid ancient practice? Only in modern times have scholars realized that some ancient discoveries, such as the Papyrus Amherst 63, were exactly what the Book of Mormon describes – Egyptian text used to write Hebrew words. (Tvedtnes & Ricks, Notes and Communications: Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters, 1996)

WITHOUT A CAUSE – In 3 Nephi when Jesus gives the Book of Mormon rendition of the Sermon on the Mount, it removes “without a cause” from the phrase “Whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause [eikei] shall be in danger of the judgment.” This doesn’t match the King James Version of the Bible, but after Joseph’s death, older Greek manuscripts of Matthew 5:22 were found with the phrase “without a cause” missing – just like in the Book of Mormon rendition. (Welch J. W., A Steady Stream of Significant Recognitions, 2002)

AN ANCIENT LITERARY GENRE: THE FAREWELL ADDRESS – Recent biblical scholars have identified a previously unknown type of literary genre called the farewell address. There are 20 specific elements that can be used in a farewell address. While this tradition was apparently well known and widespread in ancient times, that knowledge was lost. Therefore, somebody simply copying the style of the Bible would not know to include these elements appropriately since this is a new field of study. In the Book of Mormon, King Benjamin’s speech has been found to contain 16 of the farewell elements. That’s more than the farewell addresses by Paul or Socrates. (Welch J. W., A Steady Stream of Significant Recognitions, 2002)

ONE IN A TRILLION ODDS – Scientists and researchers at Berkeley and BYU developed a method for identifying authors by their stylistic choices, phrases, etc. This statistical analysis is sometimes called “wordprint” and this method has been used to identify previously unknown writing by Thomas Hobbes, as well as to identify the true authors behind some of the Federalist Papers, or modern works published under pseudonyms such as when J.K. Rowling secretly wrote under the name Robert Galbraith. This analysis shows that the individual books in the Book of Mormon are written by different authors, and that those authors were definitely NOT any of the people associated with the translation and publication of the Book of Mormon. (Hilton, 1990)

References

Deutsch, R., & Heltzer, M. (1995). New Epigraphic Evidence from the Biblical Period. Archaeological Center Publication, 89-90.

Hilton, J. L. (1990). On Verifying Wordprint Studies: Book of Mormon Authorship. BYU Studies, 1-19. Retrieved from http://davies-linguistics.byu.edu/ling485/for_class/30.3Hilton.pdf

Palka, J. W. (2010). The A to Z of Ancient Mesoamerica. Rowman & Littlefield.

Parry, D. W. (2002). Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon. In D. W. Parry, D. C. Peterson, & J. W. Welch, Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon. Maxwell Institute.

Parry, D. W. (2002). Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon. In D. W. Parry, D. C. Peterson, & J. W. Welch, Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon (p. Chapter 7). Provo: FARMS.

Skousen, R. (1994). The Original Language of the Book of Mormon: Upstate New York Dialect, King James English, or Hebrew? Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, 28-38.

Stubbs, B. D. (2015). Exploring the Explanatory Power of Semitic and Egyptian in Uto-Aztecan. Provo: Grover Publications.

Tvedtnes, J. A. (1991). The Hebrew Background of the Book of Mormon. In J. L. Sorenson, & M. J. Thorne, Rediscovering the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

Tvedtnes, J. A., & Ricks, S. D. (1996). Notes and Communications: Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters. Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, 156 – 63.

Tvedtnes, J. A., Gee, J., & Roper, M. (2000). Book of Mormon Names Attested in Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions. Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, 9(1), 40-51, 78-79.

Welch, J. (1992). “Thieves and Robbers”. In J. Welch, Reexploring the Book of Mormon (pp. 248-249). Salt Lake: Deseret Book.

Welch, J. W. (2002). A Steady Stream of Significant Recognitions. In D. W. Parry, D. C. Peterson, & J. W. Welch, Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon. Maxwell Institute.

Welch, J. W. (2003). How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829 When the Book of Mormon Was Translated. FARMS Review, 47-80.

Yadin, Y. (1965). Bar-Kokhba. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.